Meniscal & Labral Tears

What is the Meniscus and the Labrum?

The meniscii of the Knee are two ring shaped cups of fibrocartilage that help the two main bones of the knee fit together congruently.

There is a Labrum in the Shoulder and Hip joint, and these are ring shaped cups of fibrocartilage that deepen these ball and socket joints.

Overall, these tissues share many similarities in structure and function.

- They are all made of FIBROCARTILAGE, which is smooth and spongy to resist both compressive and shear forces.

- They are all designed to assist with STABILITY of the joints they are found in by DEEPENING the sockets of those joints.

- They have a limited blood supply but a good nerve supply- this usually results in pain with very slow healing if at all

Knee Meniscal Tears

The knee joint is made up of 3 compartments that help spread load and maintain smooth frictionless motion- one inner/media, one outer/lateral and one patellofemoral or knee cap.

They are all connected as one joint by a capsule that surrounds them and keeps the joint fluid flowing around all the ends of cartilage.

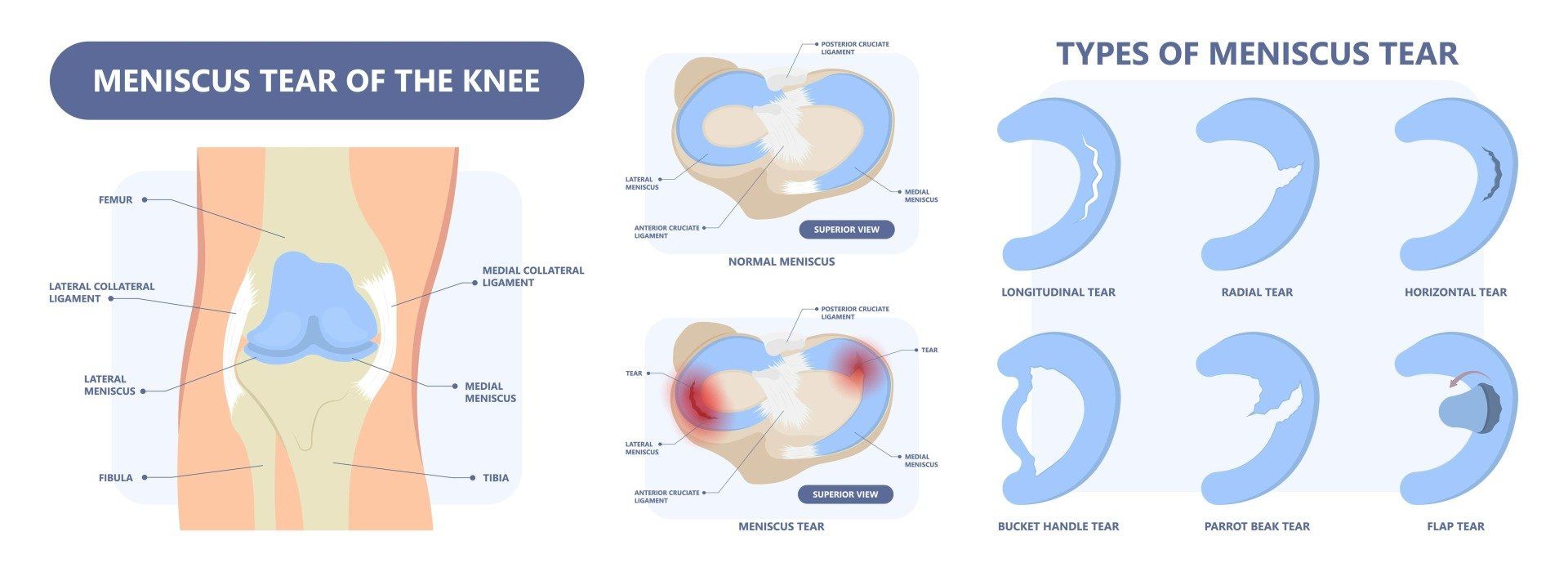

The menisci of the knee are 2 horseshoe shaped washers that help the round bones of the thigh or femur fit snuggly onto the flat bone of the shin or tibia, and this makes up the knee

Like most soft tissues they are made up of collagen fibers that form a special kind of hybrid tissue called fibro-cartilage, which is smooth and glossy like the cartilage that lines our joints called articular cartilage BUT with more thickness to resist compressive impact forces and more flexibility so it can resist stretching or tensile forces 1

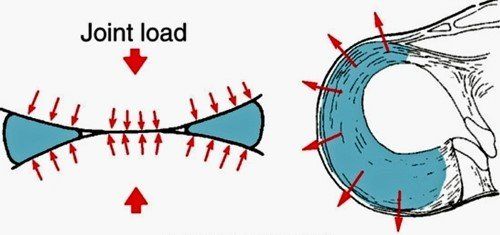

The meniscus has a unique architecture of collagen that allows it to resist rotational forces and to absorb vertical forces by acting like a rubbery hoop.

In effect, the meniscus creates stability and protects the underlying cartilage that lines the bones. even Partial meniscectomy increases the risk of knee osteoarthritis by about 5 fold. 2–4

Its blood supply is very important to understand because it comes from the outside in. This means that meniscal tears in the outer third of the meniscus have the best chance of healing, while tears along the inner rim have a poor chance.

This has a critical importance to whether a meniscal tear is appropriate for suture repair in the case of a good blood supply, or partial meniscectomy or debridement in the case of a poor blood supply.

Symptoms & Mechanisms of Meniscal Injury

Acute meniscus tears can occur in younger patients with compression/rotation), but they are unusual in isolation- many of these occur with other ligament injuries.

We much more commonly see chronic meniscal tears, which are more appropriately termed wear than tear and occur with ageing. 5,6

They are usually part of the spectrum of osteoarthritis and surgery for these has been shown to be unhelpful in most cases. 7–12

Patients will generally have pain that localizes to the side of their meniscal tear, swelling of the joint and pain with any loading/twisting movements.

Whether acute or chronic, if patients are having mechanical symptoms of locking, painful clicking, or giving way of the knee- a surgical opinion should be obtained.1

There are a variety of different patterns of meniscal tears.

Peripheral tears occur toward the areas with more blood supply and when they are painful or unstable, a surgical opinion should be obtained.

Tears can progress and become unstable Bucket Handle tears where a section flips in toward the middle of the joint.

Radial tears involve the inner margin of the meniscus which has a poor blood supply. A parrot beak tear is just an extension of this tear.

Complex tears are a combination of tear orientations usually affecting the inner avascular margin of the meniscus.

Horizontal, degenerative tears occur as part of the spectrum of tissue wear. They can lead to pain but are not repairable. Sometimes fluid from the knee joint can leak through the plane of a horizontal tear to gradually form a perimeniscal cyst (see video animation above).

Treatment Options for Meniscal Tears

The first line treatment for stable meniscal tears that aren’t displaced and causing locking of the knee is non-surgical approach including relative rest, optimal loading, and sometimes anti-inflammatory treatments.

When the pain and swelling are impeding the ability to perform even very basic strength exercises, a course of oral anti-inflammatories or the use of injection adjuncts can be very effective to settle pain and create an opportunity for re-development of strength 13,14 If cortisone is used it should be used sparingly as a one-off injection, as multiple injections in short succession have been shown to accelerate cartilage loss 15

Biomechanical assessment and awareness of aggravating movements is very helpful to maximise recovery.16–19

After a minimum 8-week period of this approach, a surgical opinion is warranted.

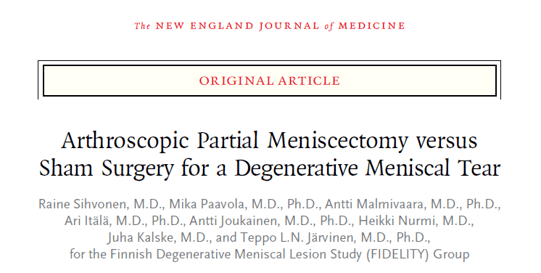

This is because there have been multiple, consistent studies published in the modern era that show that there is no overall difference between sham surgery or no surgery for patients with stable meniscal tears.

It is now standard of care to recommend a non-operative approach in the first instance for stable meniscal tears 20

Of course, this can only tell us about the average and not the individual response to surgery, so this needs to be an individual decision.

Labral Tears of the Shoulder (Glenoid Labrum)

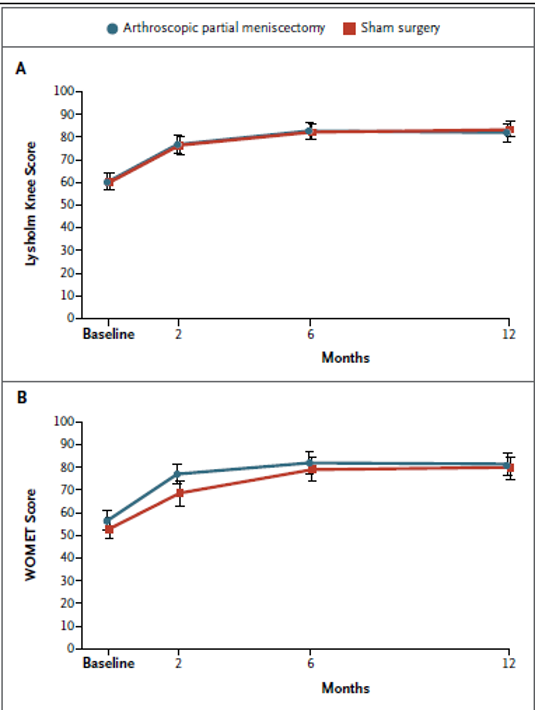

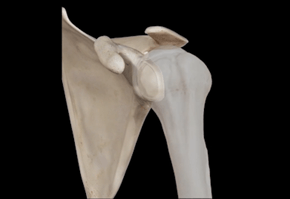

The glenoid labrum of the shoulder is a rubbery tissue that lines the socket like a white washer and deepens it, which improves the stability of the shoulder. The shoulder is a unique joint in that it is inherently mobile at the expense of stability.

The labrum can be torn acutely with an instability episode of the shoulder, as shown in the video above.

But it can also develop chronic tears that are caused by gradual tissue overload, especially in people who have hypermobile joints that are able to overstretch tissues easily.

You can see in detail in the video above that the biceps tendon attaches to the top part of the labrum. This tendon is an important secondary stabilizer that straps the ball down into the socket and prevents it sliding forward. During activities like throwing a ball or climbing the tendon can pull forcefully at the labrum. If the labrum peels away from the socket, it can be painful every time the biceps tendon is loaded.

Chronic Labral tears are a difficult and controversial area of Sports Medicine because many patients will have these tears but have no pain. 21

A chronic labral tear in of itself may not cause any pain unless it is being repetitively loaded or it is very unstable and moving around.

Common signs of labral tears include persistent deep seated shoulder pain, clicking and clunking, and a sense of instability and distrust of the shoulder.

Clinical tests are not very reliable but an MRI with contrast called an arthrogram, often combined with a steroid injection for pain relief, can pick up about 90% of labral tears at the same time as providing a platform of pain relief to allow some rehabilitation exercise. 22

Once the labrum is torn, the shoulder loses a degree of stability. It loses its snug fit and the seal around it so that micro-movement occurs. This can lead to shoulder pain from secondary sources such as imbalanced forces and bursitis or rotator cuff irritation as the ball wobbles around more in its socket.

In chronic labral tears, especially in patients with hypermobile shoulders, a period of rehabilitation of 4-6 months is warranted before considering surgical options but activity demands strongly affect the decisions around this controversial area. 23

Labral Tears of the Hip (Acetabular Labrum)

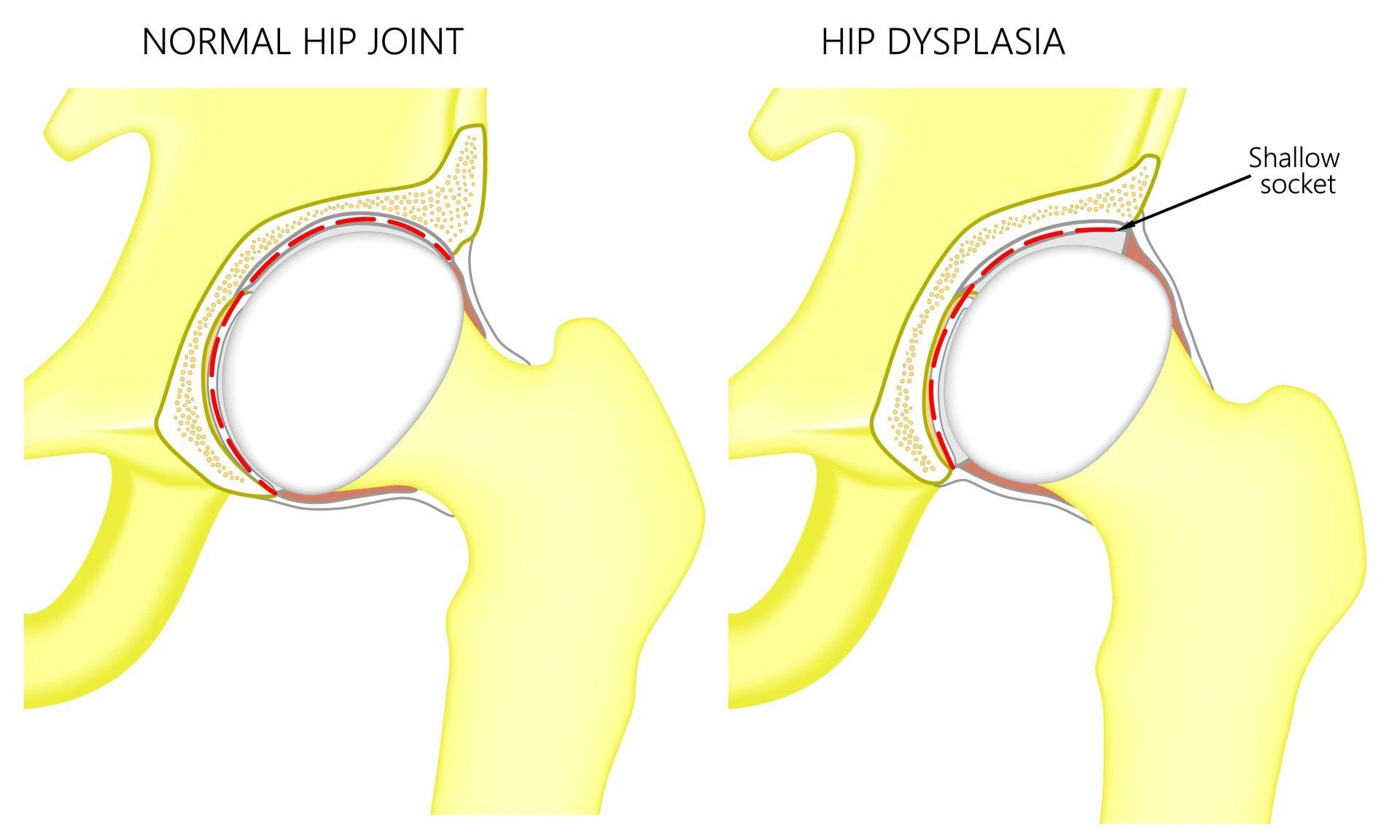

The labrum of the hip, known as the acetabular labrum is a biological washer that improves the congruence and stability of the joint.

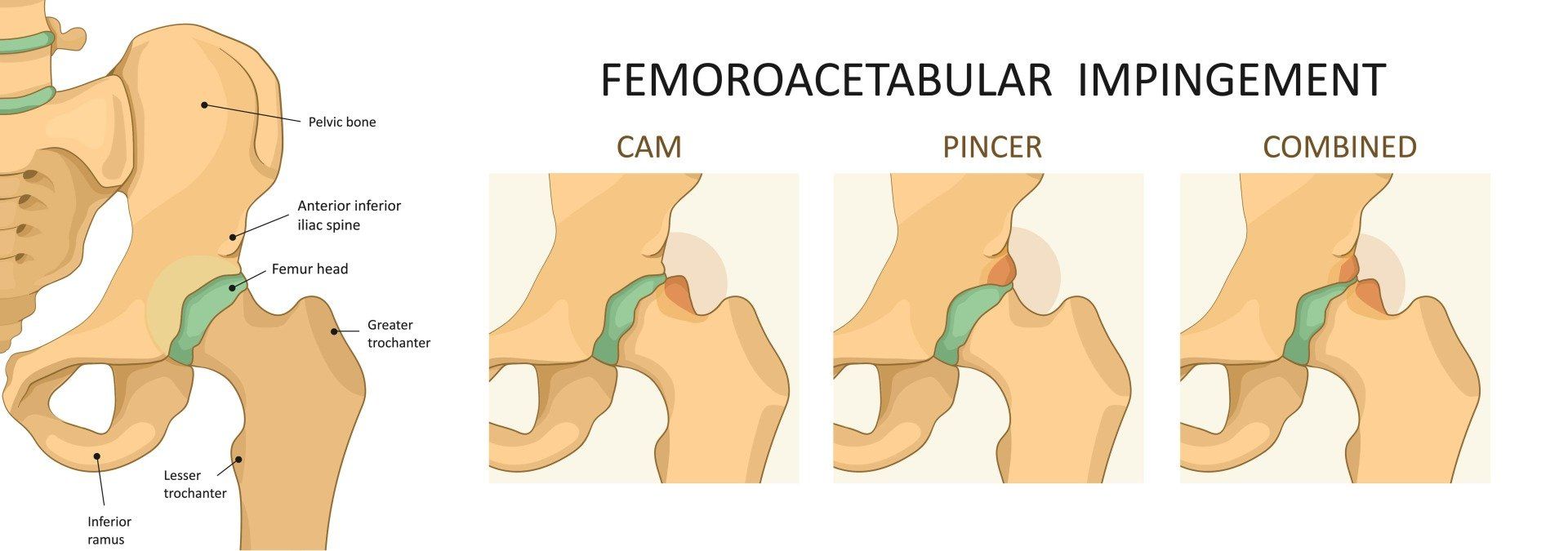

There are several reasons why the labrum may develop a tear, but one of the most common reasons is the shape of the hip joint lending itself toward abrasion of the labrum.

Some patients will be born with a shallower hip socket, a condition known as developmental dysplasia of the hip, and put increased load on the edge of the socket.

Others will develop bony bumps around their growth plates during adolescence and this leads to pinching or impingement of the soft tissues at the front of the socket, including the labrum between those bony bumps as the knee moves up toward the chest. This is called FAI or hip impingement syndrome. 24

One of the challenges faced by clinicians is that Tears of the labrum are not always painful. One prospective study showed that 40% of patients who had a symptomatic labral tear had completely asymptomatic tears on their other side. 25, 26 As many as 55% of athletes have the criteria for FAI on scans, but only a small proportion have FAI syndrome.

Reference List

1. Makris EA, Hadidi P, Athanasiou KA. The knee meniscus: structure-function, pathophysiology, current repair techniques, and prospects for regeneration. Biomaterials. 2011 Oct;32(30):7411–31.

2. Eichinger M, Schocke M, Hoser C, Fink C, Mayr R, Rosenberger RE. Changes in articular cartilage following arthroscopic partial medial meniscectomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc Off J ESSKA. 2016 May;24(5):1440–7.

3. Papalia R, Del Buono A, Osti L, Denaro V, Maffulli N. Meniscectomy as a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2011;99:89–106.

4. Roemer FW, Kwoh CK, Hannon MJ, Hunter DJ, Eckstein F, Grago J, et al. Partial meniscectomy is associated with increased risk of incident radiographic osteoarthritis and worsening cartilage damage in the following year. Eur Radiol. 2017 Jan;27(1):404–13.

5. Howell R, Kumar NS, Patel N, Tom J. Degenerative meniscus: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment options. World J Orthop. 2014 Nov 18;5(5):597–602.

6. Lange AK, Fiatarone Singh MA, Smith RM, Foroughi N, Baker MK, Shnier R, et al. Degenerative meniscus tears and mobility impairment in women with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007 Jun;15(6):701–8.

7. Hwang YG, Kwoh CK. The METEOR trial: no rush to repair a torn meniscus. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014 Apr;81(4):226–32.

8. Herrlin S, Hållander M, Wange P, Weidenhielm L, Werner S. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc Off J ESSKA. 2007 Apr;15(4):393–401.

9. Herrlin SV, Wange PO, Lapidus G, Hållander M, Werner S, Weidenhielm L. Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc Off J ESSKA. 2013 Feb;21(2):358–64.

10. Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, de Chaves L, Cole BJ, Dahm DL, et al. Surgery versus Physical Therapy for a Meniscal Tear and Osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013 May 2;368(18):1675–84.

11. Yim J-H, Seon J-K, Song E-K, Choi J-I, Kim M-C, Lee K-B, et al. A comparative study of meniscectomy and nonoperative treatment for degenerative horizontal tears of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med. 2013 Jul;41(7):1565–70.

12. Stensrud S, Risberg MA, Roos EM. Effect of exercise therapy compared with arthroscopic surgery on knee muscle strength and functional performance in middle-aged patients with degenerative meniscus tears: a 3-mo follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015 Jun;94(6):460–73.

13. Charlesworth J, Fitzpatrick J, Perera NKP, Orchard J. Osteoarthritis- a systematic review of long-term safety implications for osteoarthritis of the knee. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019 Apr 9;20:151.

14. Conservative vs. surgical approach for degenerative meniscal injuries: a systematic review of clinical evidence [Internet]. European Review. 2020 [cited 2021 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.europeanreview.org/article/20651

15. Zeng C, Lane NE, Hunter DJ, Wei J, Choi HK, McAlindon TE, et al. Intra-articular corticosteroids and the risk of knee osteoarthritis progression: results from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Jun;27(6):855–62.

16. Turpin KM, De Vincenzo A, Apps AM, Cooney T, MacKenzie MD, Chang R, et al. Biomechanical and Clinical Outcomes With Shock-Absorbing Insoles in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: Immediate Effects and Changes After 1 Month of Wear. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012 Mar;93(3):503–8.

17. Hunter D, Gross KD, McCree P, Li L, Hirko K, Harvey WF. Realignment treatment for medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis: randomised trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Oct;71(10):1658–65.

18. Bennell KL, Hunt MA, Wrigley TV, Hunter DJ, McManus FJ, Hodges PW, et al. Hip strengthening reduces symptoms but not knee load in people with medial knee osteoarthritis and varus malalignment: a randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010 May;18(5):621–8.

19. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Nov 1;27(11):1578–89.

20. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, et al. Arthroscopic Partial Meniscectomy versus Sham Surgery for a Degenerative Meniscal Tear. N Engl J Med. 2013 Dec 26;369(26):2515–24.

21. Rowan KR, Andrews G, Spielmann A, Leith J, Forster BB. MR shoulder arthrography in patients younger than 40 years of age: frequency of rotator cuff tear versus labroligamentous pathology. Australas Radiol. 2007 Jun;51(3):257–9.

22. Smith TO, Drew BT, Toms AP. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic test accuracy of MRA and MRI for the detection of glenoid labral injury. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012 Jul;132(7):905–19.

23. Calcei JG, Boddapati V, Altchek DW, Camp CL, Dines JS. Diagnosis and Treatment of Injuries to the Biceps and Superior Labral Complex in Overhead Athletes. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018 Jan 17;11(1):63–71.

24. Tijssen M, van Cingel R, Willemsen L, de Visser E. Diagnostics of femoroacetabular impingement and labral pathology of the hip: a systematic review of the accuracy and validity of physical tests. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg Off Publ Arthrosc Assoc N Am Int Arthrosc Assoc. 2012 Jun;28(6):860–71.

25. Frank JM, Harris JD, Erickson BJ, Slikker W, Bush-Joseph CA, Salata MJ, et al. Prevalence of Femoroacetabular Impingement Imaging Findings in Asymptomatic Volunteers: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2015 Jun 1;31(6):1199–204.

26. Vahedi H, Aalirezaie A, Azboy I, Daryoush T, Shahi A, Parvizi J. Acetabular Labral Tears Are Common in Asymptomatic Contralateral Hips With Femoroacetabular Impingement. Clin Orthop. 2019 May;477(5):974–9.