Runner's Knee

Introduction to Runner’s Knee

Runner's Knee is similar but different to “Jumper’s Knee”. They can co-exist.

The medical term for Runner’s Knee is

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. This refers to pain under and around your kneecap. Runner’s knee has a number of synonyms including anterior knee pain syndrome, patellofemoral maltracking, movie-goers knee, and chondromalacia patella- all referring to pain generated by anatomical structures around the joint between your knee-cap (patella) and the groove formed by the lower part of the thigh bone (trochlea). As the name suggests, runner’s knee is a common complaint among runners, jumpers, and other athletes such as skiers, cyclists, and soccer players.

Anatomy of Runner’s Knee

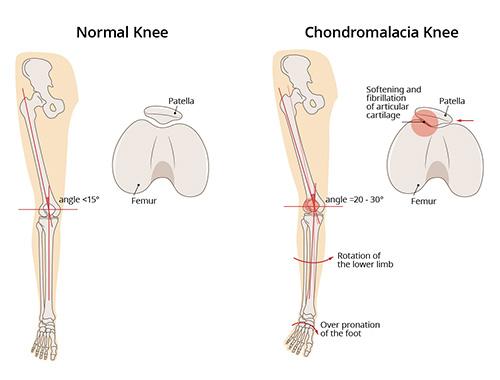

The patellofemoral joint is the joint between the kneecap and the groove that is formed at the end of the thigh bone called the trochlea.

This joint enjoys the thickest articular cartilage in the body but it needs this cartilage to absorb both compressive and shear forces.

Every time you bend your knee, the cartilage surfaces engage at about 30 degrees of knee bend. When you lunge or go up or down stairs – this joint must absorb 10-12 times your body weight in force.

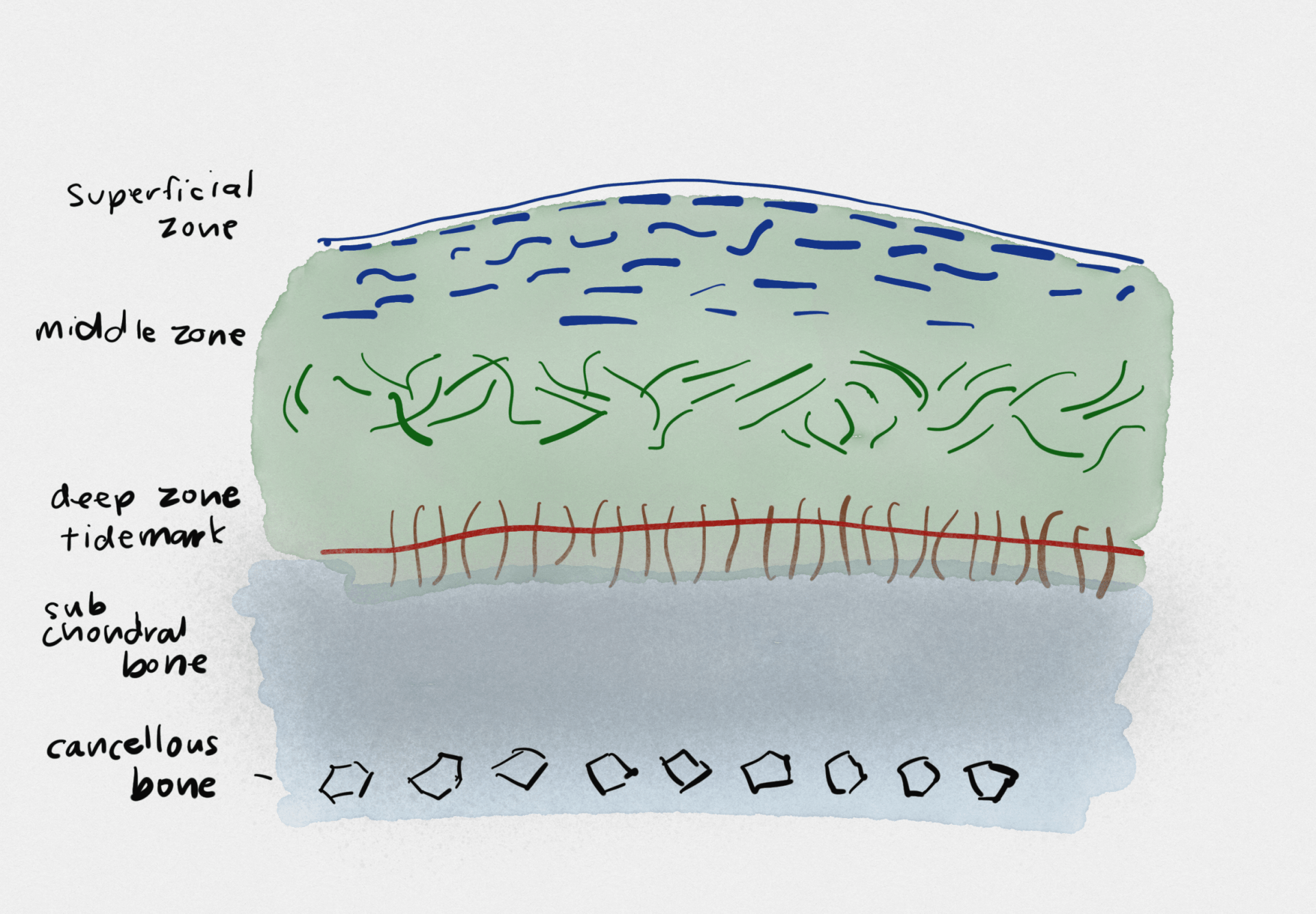

Hyaline cartilage has a very unique architecture so that the top layers have collagen fibers oriented horizontally to resist shear forces, while the deeper layers have the collagen pointing vertically to absorb the compressive and impact forces.

When the kneecap does not track smoothly in its groove, it can lead to increased shear forces on the cartilage which can abrade irritate the cartilage.

Even though there is no deep or significant damage to the cartilage, the excessive friction on the surface layers can lead to pain (see Superficial Zone below), swelling and stiffness that often limits exercise capacity and persists for months.

Causes of Runner’s Knee

Runner’s knee can result from poor alignment of the kneecap, complete or partial dislocation, overuse, tight or weak thigh muscles, flat feet, or even direct trauma to the knee. It is important to realise that it is more of an inflammatory response – where the knee joint lining detects small, microscopic cartilage fragments, rather than any significant visible cartilage damage. Cartilage has no nerve endings and so we know that it does not generate the pain. Patellofemoral pain often comes from inflamed soft tissues (fat, ligaments and capsular tissue) and irritation or softening of the cartilage that lines the underside of the kneecap. The cartilage itself has no nerve endings, but the underlying bone has lots of nerve-endings and becomes exposed when the cartilage thins or is injured. Pain in the knee may be referred from or contributed to by other parts of the body, such as the feet, back or hip.

Symptoms of Runner’s Knee

The classic symptom of runner’s knee is a dull aching pain underneath the kneecap while doing anything that loads the knee-cap (patellofemoral) joint- including walking up or downstairs, squatting, lunging or kneeling. One of the old names for the condition is "movie-goers" knee, because a common complaint is that pain is worse after standing up from prolonged sitting.

Diagnosis of Runner’s Knee

Most of the features of patellofemoral pain syndrome are clinical and functional because it is a dynamic process. A classical history of pain, presence of the known risk factors, pain during a squat movement, tenderness of the edges of the patella and a grinding sensation during movement all support the diagnosis.

The major diagnoses to exclude are instability of the kneecap (that is, dislocations) and a condition called excessive lateral pressure syndrome where there is a much more severe form of mechanical overload of the outer part of the patella due to malalignment (this often requires surgery, while runner's knee does not).

Imaging findings such as a high-seated knee cap or thinning of the cartilage on MRI also support the diagnosis of patellofemoral maltracking but are not essential for diagnosis

Dr Samra will assess your specific risk factors and contributors including your running/walking biomechanics and "weak links" in the chain from top to bottom.

Risk Factors - Who is at Risk?

There are many biomechanical, anatomical and load-related factors that predispose a person to patellofemoral pain syndrome.

- A kneecap that sits higher or a smaller kneecap

- A flatter groove for the kneecap- called trochlea dysplasia

- Alignment that tends to make the patella shift or tilt to the outer side of the knee- increases the contact forces on this area.

- Females are at higher risk

- Poor stabilizer muscle activity around the knee and hip

- Short hamstrings and weak quadricep muscles

Treatment of Runner’s Knee

Treatment of Runner’s Knee can begin immediately after the injury is sustained. Common first-response treatments for jumper’s knee may include:

- Pain medication - nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) can relieve some pain or discomfort associated with jumper’s knee (ibuprofen or naproxen)

- POLICE - To reduce acute pain and swelling around an injured area.

- Protect - support and position the injury in a way that doesn't worsen it.

- Optimal Loading - rehabilitation begins as soon as the injury occurs. It is a matter of finding non-exacerbating load to stimulate and enhance tissue recovery.

- Ice - for comfort and pain relief. 10 minutes as often as every 4-6 hours for the first 2 days.

- Compression - to control swelling and inflammation.

- Elevation - the most potent means of reducing swelling is lifting the limb above the level of the heart.

- Activity Modification - Pausing aggravating athletic activities until the symptoms of jumper’s knee have reduced or resolved.

Recommended Treatments for Runner’s Knee

The best consensus guidelines that summarise the evidence tell us that Treatment for PFPS must be individualised based on a full assessment of the patient’s specific contributors to their pain. Even when there is marked wear of the cartilage and osteoarthritis of the patellofemoral joint- non-surgical treatments should be targeted first line because they can make a big difference to pain.

Evidence shows that multimodal treatment programs lasting at least 6 weeks have a very significant benefit for pain and function

These programs incorporate education about the pain and most suitable activities, customised patella taping which usually makes a significant difference, sometimes orthotics and oral anti-inflammatories.

In recalcitrant cases, especially when the fat pads around the knee are very sensitive or inflamed, a single cortisone injection can provide marked pain relief. All of this is to promote specific progressive resistance training of the quadriceps and stability exercises as well as hamstring and quadriceps lengthening exercises which are the most important aspects of long-term recovery. In summary, multimodal treatment may include:

- Exercise training: Once pain is controlled, exercise to strengthen the stabilising muscles of the hip and knee can improve your exercise tolerance and reduce the symptoms of runner’s knee. Core stability (pilates-style) exercises are often a missing link that helps people prevent pain coming back by improving movement control and quality.

- Taping: An adhesive tape is applied over the patella, to alter the kneecap alignment and movement. Taping of the patella may reduce pain by more than 50% immediately

- Bracing: A physician may recommend stabilizing the patella with either a brace or athletic tape to keep it in place during exercise training.

- Orthotics: Shoe inserts (over the counter or customised) may be prescribed for those with arches that fall in (pronate), and this can help relieve the pain.

- Anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) - used for a short 1-2 week period, can reduce pain and swelling to promote rehabilitation

- Injection Therapies: Corticosteroid (cortisone) injections may be used to reduce pain and inflammation, but are only used to provide a window of opportunity to reduce pain so that your own stabilising muscles can be retrained. Pain inhibits these muscles and perpetuate a maltracking patella and pain.

- Platelet-rich plasma therapy: This practice, also known as PRP, involves injecting the site of the injury with the patient's own platelet-rich plasma in an effort to accelerate healing.

- A patient may need to undergo other treatments to ensure the ongoing health of the knee, and

activity modification with pacing of exercise is often required to find the right dose of load to the joint during recovery.

- Pain education from a biopsychosocial model is important in addressing fear of movement from unhelpful thinking, such as that pain means tissue damage. It is important to realise that the body is very resilient and dynamic. It is constantly healing and adapting to microscopic damage, and exercise helps promote this adaptation so long as it does not exacerbate pain.

Additional Treatments for runner's Knee

In some rare cases, you may need surgery that includes:

- Arthroscopy: A small camera and several surgical tools are inserted into the knee joint and used to remove small fragments or damaged tissue. Some patients will have an extra fold of joint tissue called a plica that rubs on the inside of the knee cap joint and this can be shaved

- Realignment Surgery: This method can be used to remove or realign the patella thus reducing the abnormal pressure on cartilage and supporting structures around the front of the knee. There are a number of options, depending on the specific cause of maltracking

Prevention of runner’s Knee

- If you are overweight, you may need to control your weight to avoid overstressing your knees

- Gradually increase the intensity of your workouts and avoid running on hard surfaces

- Wear proper fitting good quality running shoes with good shock absorption

- Avoid running straight down hills; instead, walk down it or run in a zigzag pattern

- If in doubt, speak to your Physiotherapist and sit down to plan a regular program that promotes strength and control exercises. If you have not tried customised taping as a starting point, this should be explored.

- Core stability exercise is often used to treat back pain. It is under-rated in preventing upper and lower body injuries.

- Programs such as the FIFA-11 provide a good starting point as evidence-based warm ups that have been shown to lower injury risk