Stress Fractures

What is a stress fracture?

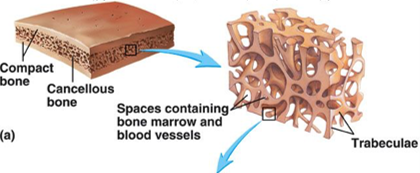

Bone is living tissue which is constantly being removed and created. It is normal for force through a bone to cause microscopic damage that the body quickly repairs. If the damage is too much or too repetitive or the body’s repair systems are compromised (fatigue, illness, lack of recovery), then a particular bone can become progressively weakened in one spot.

Stress injuries can be anything from a slight weakening/bruising of the bone to a displaced fracture (and everything in between). With the development of improved imaging technology (high resolution MRI), we are now picking up bone stress injuries that could not previously be seen on other scans.

How do stress fractures occur?

Sometimes the causes for a stress fracture are obvious – such as athletes suddenly increasing training intensities or volumes. But often stress fractures can occur without an obvious escalation in training or clear cause. This is because there can be multiple internal and external contributing factors at play. Some possible warning signs can include missed or late periods in female athletes, gastrointestinal distress or weight-loss.

A very common mistake athletes make in self-diagnosing is made in the following statement: “I couldn’t possibly have a stress fracture, I have only been training at low volumes/intensity”. Training volume is just one of the many potential contributing factors and many athletes and non-athletes develop stress fractures seemingly innocuously with very low activity levels at times.

What are the symptoms of a stress fracture?

The most reliable feature to find when examined is direct tenderness over a bone – such as a metatarsal (foot) or tibia (shin).

Plenty of stress fractures still won’t be so obvious.

Hip and Spine stress fractures can produce vaguely located pain and no localised tenderness.

Continuing to push through pain can lead to much more severe fractures, and some bones and locations are higher risk for dire consequences.

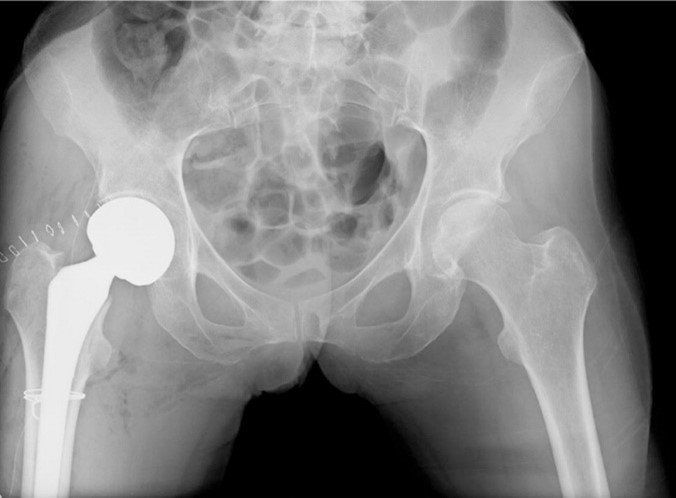

For example, stress fractures of the hip can lead to the development of AVN (avascular necrosis), where damage to the blood supply of the hip can lead a patient to require a hip replacement.

Not all stress fractures behave in the typical matter but pain, that is worse with increased weight-bearing activity is common.

If you also have localised tenderness to touch over a bony area, the suspicion is higher still.

You need to be examined by an experienced professional to accurately assess this.

An example of a worst case scenario- Because of the effects on blood supply, is an undiagnosed superior femoral neck stress fracture can lead a young athlete to require a hip replacement. 3

How is a stress fracture diagnosed?

Sometimes an expert physician can diagnose a stress fracture just on examination but more often the assessment leads to a high suspicion that needs to be confirmed with a scan. Scans can also be helpful in determining the severity of a stress injury which will influence how it is treated. Sport and Exercise Physicians are the only specialist medical doctors that have the training and experience to deal with all types of athletic stress injuries.

Whenever a fracture occurs with minimal trauma it raises questions about bone health in general- so a comprehensive medical workup is needed- and that is really where Sport and exercise physicians are specifically trained 4,5

While the treatment is generally some form of rest or immobilisation, an assessment of markers of bone health and metabolic as well as biomechanical contributors to the stress fracture need to be considered.

How do you treat a stress fracture?

All athletic bone stress injuries should be seen by a Medical professional. Often we need to investigate to see if there is an underlying medical cause such as a hormonal or nutrient problem that has led to the injury – and if a problem is identified that will also require treatment.

Not all stress fractures are the same. Some bones have a fantastic capacity to repair themselves and need less attention than others. Some can be extremely difficult to manage and repair and early expert care can prevent lifelong repercussions.

Your management plan will be based on your individual fracture, risk factors and the best available scientific evidence.

Just as with any other injury, the process of recovery starts with optimal loading, and gradual upgrade in activities with both stimulus and substrate for tissue healing and remodeling.

It requires regular review with a physio or allied health professional, with summative medical reviews at key milestones to ensure progress is being made 6

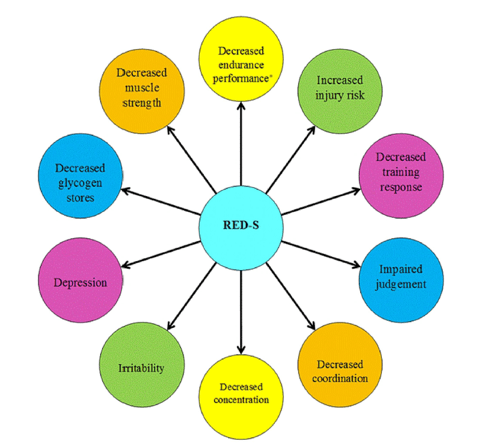

If there is a relative deficiency of energy after the body has used its energy on exercise and core functions, other bodily functions to do with reproduction, bone health, mental health and gut health can be compromised. Although loss of menstruation is a common feature of this energy deficiency, relative energy deficiency occurs in both men and women 4

Where do stress fractures commonly occur?

The most common sports for stress fractures occur in the bones of the feet (metatarsals, navicular, heel bone) and the shin (tibia and fibula). These are also the most common sites in people who do running sports but almost any bone can get a stress fracture depending on the activity. Fast bowlers commonly get stress fractures of their spine, rowers can get them in the ribs and tennis players can get them in the arm.

How long do stress fractures take to heal?

There is no set amount of rest for all stress fractures. Some heel very quickly and are very forgiving, others can take much longer. For serious athletes and even the every day person, it is sensible to see a Sports and Exercise Physician to work out the appropriate treatment for your specific type of stress injury.

Reference List

1. Miller T, Kaeding CC, Flanigan D. The classification systems of stress fractures: a systematic review. Phys Sportsmed. 2011 Feb;39(1):93–100.

2. Mallee WH, Weel H, van Dijk CN, van Tulder MW, Kerkhoffs GM, Lin C-WC. Surgical versus conservative treatment for high-risk stress fractures of the lower leg (anterior tibial cortex, navicular and fifth metatarsal base): a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Mar;49(6):370–6.

3. Robertson GAJ, Wood AM. Lower limb stress fractures in sport: Optimising their management and outcome. World J Orthop. 2017 Mar 18;8(3):242–55.

4. Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, et al. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad--Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med. 2014 Apr;48(7):491–7.

5. Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, et al. The IOC relative energy deficiency in sport clinical assessment tool (RED-S CAT). Br J Sports Med. 2015 Nov;49(21):1354–1354.

6. Diehl JJ, Best TM, Kaeding CC. Classification and Return-to-Play Considerations for Stress Fractures. Clin Sports Med. 2006 Jan;25(1):17–28.