Tendon Injuries

Most Tendon Problems Respond to Optimal Exercise Loads

What is Tendinopathy?

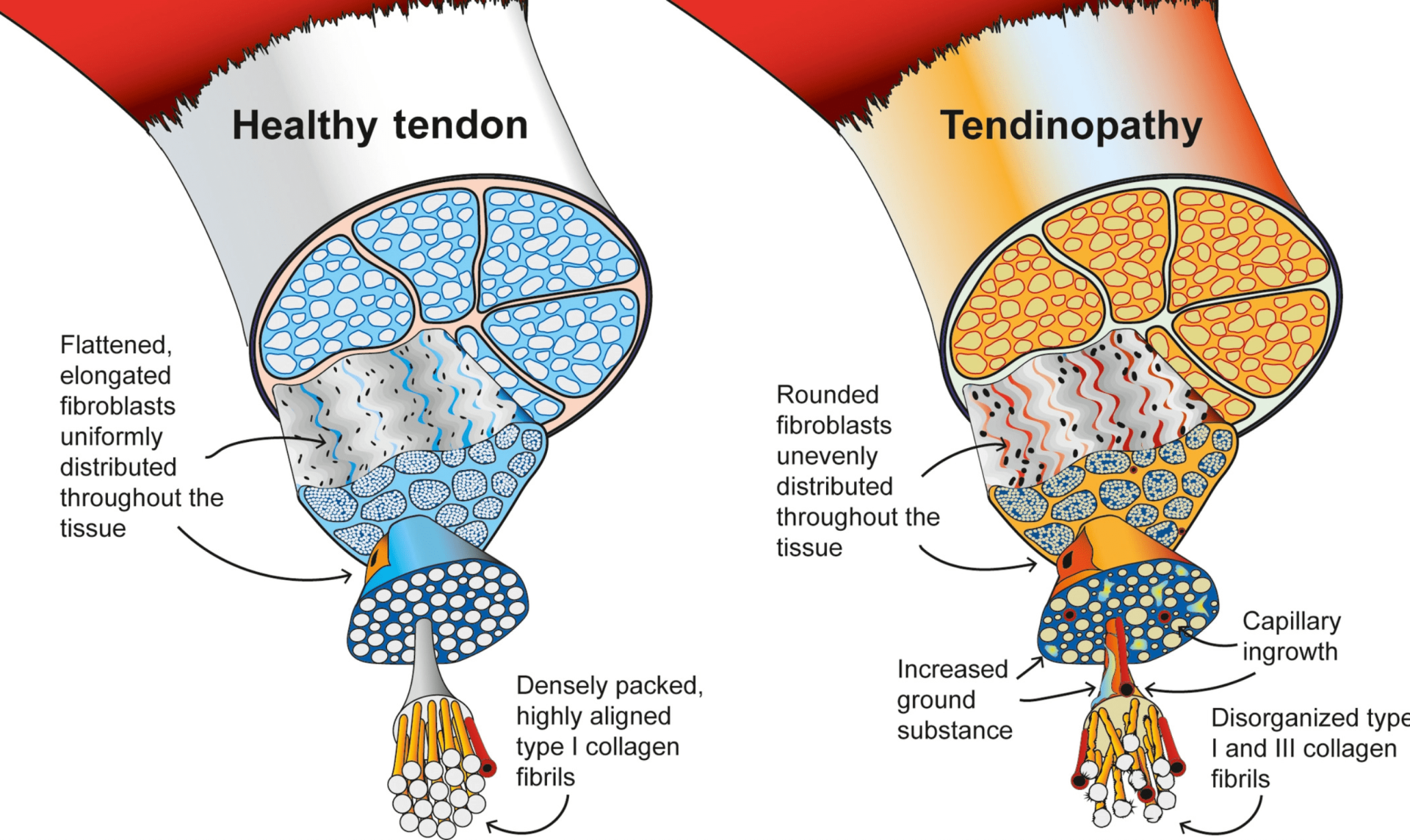

“Tendinopathy” is a broad term that includes all types of tendon damage and injury. The tendon is the strong band of tissue that muscles use to attach to the bone. They are packed with dense collagen fibres in rows that allow them to store and release energy like biological bungy cords. Like most other tissues in our bodies they adapt to the stresses placed on them, and can withstand high-magnitude and repetitive forces in most sports and exercise activities.

It is normal for tendon tissue to suffer a microscopic injury with use. Your body has an ongoing repair mechanisms that maintain and increase tendon strength as a response. If the tendon is damaged quicker than it can repair, or if there are metabolic conditions that limit the quality of repair, it may either weaken or repair poorly. Early on this can cause tendon pain. If the process continues it can lead to chronic tendon degeneration.

Symptoms & Sites of Tendinopathy

Tendinopathy often results in stiffness, pain and weakness in particular movements. Often it feels worse when initiating new movement after periods of rest like getting out of a chair or getting up in the morning.

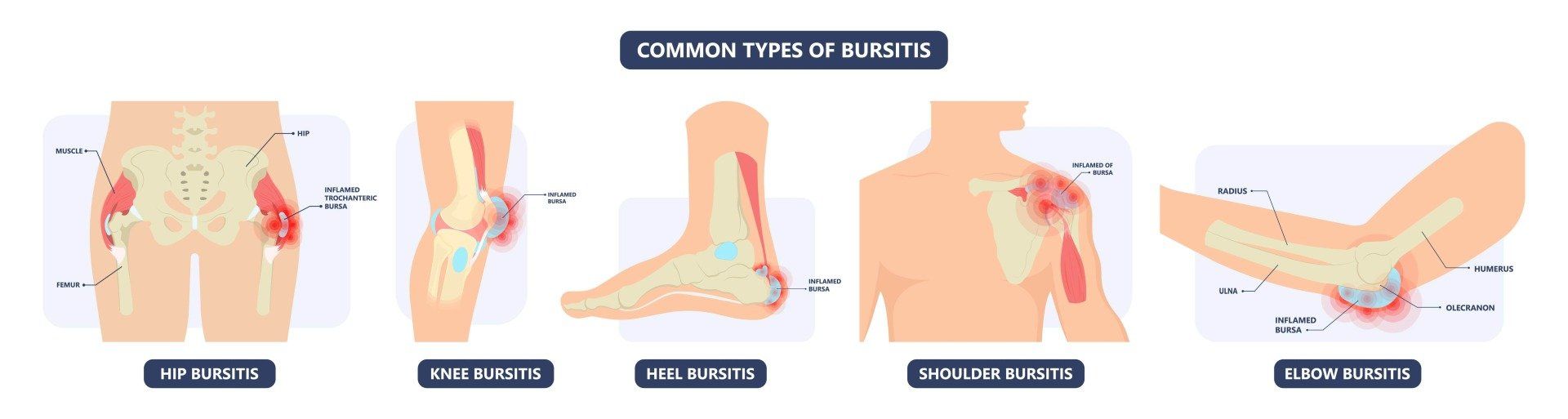

Tendon injuries can occur anywhere in the body but there are a few sites that are more prone to tendon injury than others. These tendons are usually under higher loads or are under more compressive forces, instead of the tensile forces they are designed to deal with. Common sites include the elbow (inner "golders elbow" or outer "tennis elbow"), the Achilles tendon, the patella tendon (in the knee), shoulder tendons and the hamstring tendon (in the buttock as they insert onto the sitting-bones).

Are There Other Causes Of Tendon Pain?

Absolutely! A trap that many medical professionals fall into is assuming all tendon pain is ‘tendinopathy’. Tenosynovitis (inflammation in the lining of the tendon) and Enthesitis (inflammation of the tendon insertion) are just two examples and the treatment for these is vastly different from the treatment for degenerative tendinopathy. Calcific tendinopathy is another type that can be tricky to manage.

There is a high degree of nuance and heterogeneity to these problems and as always, an expert and a thorough diagnosis made by an experienced practitioner is the key.

What Are The Different Types Of Tendinopathy?

Tendons are biological springs- storing and releasing mechanical energy to allow our muscles to move our bones. Under normal conditions, they are made up of densely packed collagen fibres in parallel and helical alignment. 1,2

When patients have mechanical overload or metabolic conditions that damage the tendons there is a continuum of pathology that occurs, and we are still learning about the relationship between structural findings and tendon pain. 3–5

Jill Cook and Craig Purdam outlined this model in 2016 where a tendon can transition anywhere along continuum from an inflamed “reactive” tendon to a tendon in disrepair that is trying to regenerate to a well and truly worn/degenerate tendon where remodelling is unlikely.

1. Reactive Tendinopathy

Jill Cook and Craig Purdam outlined this model in 2016 where a tendon can transition anywhere along continuum from an inflamed “reactive” tendon to a tendon in disrepair that is trying to regenerate to a well and truly worn/degenerate tendon where remodeling is unlikely.This is where the tendon reacts to excessive demands with pain and inflammation that has not resulted in any structural damage. Usually, the key here is load management to find a healthy middle-ground. Rest might lead to tendon weakening and a poor repair whereas continued excessive loads can lead to further aggravation and damage.

2. Tendon Disrepair

This is further along the continuum of tendon pathology and accumulated microscopic damage, where the healing process is slow. The tendon is still actively repairing and remodelling in response to the loads and resources available. Tenocytes are the smallest functioning units (cells) within a tendon, and these take over 3 months to renew to help generate new, healthy collagen tissue that can resist heavier tensile loads.

3. Degenerative Tendinopathy

When the compromised repair goes on for too long, the rate at which the tendon remodels itself diminishes leaving a poor repair with very few cells actively healing the tendon. We now accept that the part of the tendon that has the most wear (degeneration), heals far slower than the rate of improvement in symptoms- while the rest of the tendon gets stronger and thicker. Dr Sean Docking and his team of researchers at La Trobe University coined the term "making the donut bigger" to describe the way we treat these "holes" in the tendon by strengthening the rest of the more normal tendon.

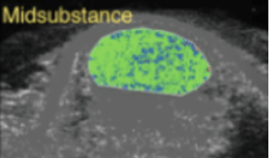

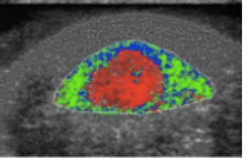

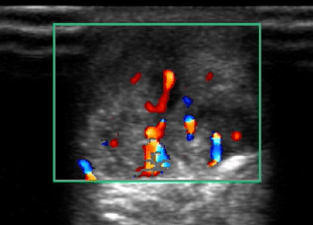

The most important treatment for any stage of tendinopathy is targeted exercises and load optimization to stimulate tendon growth and functional capacity. When there is persistence of symptoms for months despite rehabilitation exercise and presence of neovessels with evidence of flow seen on colour doppler ultrasound, it is reasonable for patients to seek adjunctive treatments. These vessels are thought to represent ingrowth that occurs into tendon, which occurs with nociceptive pain nerve endings and contributes to pain and sensitivity.

How Is Tendinopathy Diagnosed?

Tendinopathy can usually be diagnosed by an expert practitioner without the need for any further investigation. Occasionally further investigation can be required to check for other conditions or contributing factors. Dr Samra uses a dynamic point of care ultrasound to assist in diagnosis and characterisation of the tendon, and its associated blood vessels. The blood vessels (neovessels) that grow into a tendon are not normal and are accompanied by pain-producing nerves that are associated with pain.

How Is Tendinopathy Treated?

The most important step for any practitioner is to thoroughly understand the individual tendinopathy because how longstanding the problem is, what sort of loads the tendon currently tolerates and how the tendon has responded to past treatment will all greatly affect treatment. No two tendons are the same. If ever there was a medical condition where a ‘cookie-cutter’ approach was destined to fail – this is it!

Some tendons require more load, some less. Some need anti-inflammatories, some don’t. Some will benefit from injection therapies, many don’t.

Most rehabilitation programs can be divided into 3 phases, that should correspond with the physiology of tissue repair and healing:

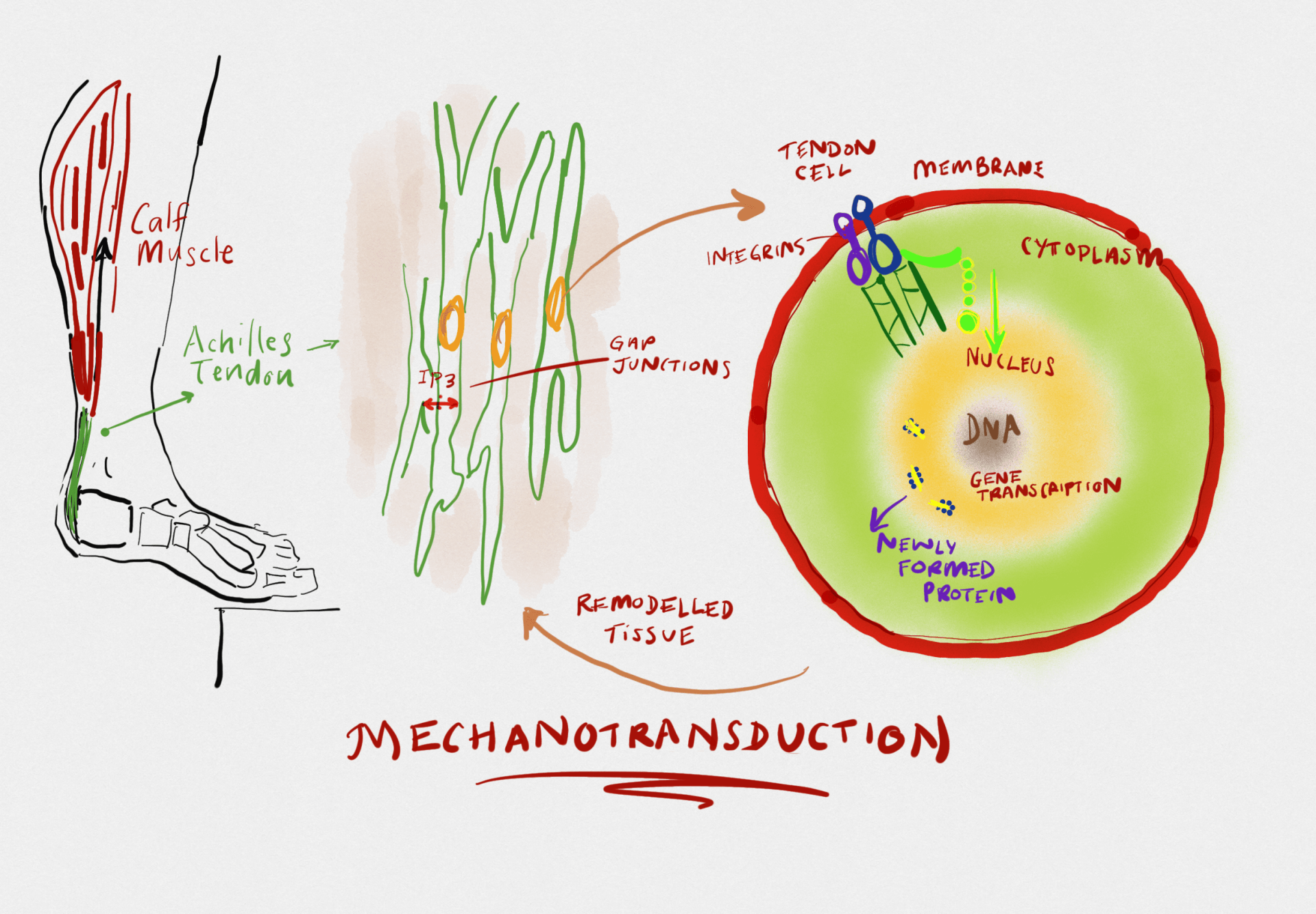

Most tendon problems respond to “mechanotherapy” – which is a fancy name for targeted rehabilitation that stimulates protein and collagen synthesis in the tendon.

When we load a tendon, the mechanical signal is converted to a chemical signal (mechanotransduction) that increases the gene expression of proteins to lay down new tendon. New Paragraph

There are 3 recent research discoveries that translate to how we treat tendon pain:

1) While there are no inflammatory cells inside worn tendons, there are inflammatory chemicals called cytokines and neuropeptides which can cause pain but also respond to treatments that reduce these. 7

2) It is not the worn/degenerate regions we are focusing on with tendon rehabilitation- we should accept that those regions will not heal in months and focus on improving strength and integrity of the rest of the tendon. One analogy used is to accept the hole in the donut but make the whole donut bigger. 5

3) Getting the right dose of exercise for the tendon to remodel and recover at the same time has having predicable and manageable pain levels is the main challenge 8,9

It’s a bit like Blackjack -- where we are trying to load the tendon enough to promote “mechanotransduction” without causing excessive pain or irritation. Starting with very simple exercises call “isometric holds” is often very well tolerated and can actually reduce tendon pain whilst improving load tolerance. 10

Here is my summary of the practical application of the latest science on tendinopathy. In most cases by the time a patient is seeing me as a specialist, they have persistent pain, tendon disrepair and degeneration- so this refers to this end of the continuum.

While over 90% of patients do well if this happens, if a patient cannot make progress, that’s the time to refer on for a Sports Physician’s review of more complex sources of pathology. Calcific tendinopathy is thought to represent a healing response in degenerative tendons with a powerful neurovascular ingrowth. 11 These forms of tendinopathy often affect the rotator cuff and Achilles and appear to respond very well to a shock wave therapy which helps break up the ingrowth of painful nerve endings using acoustic energy.12,13

Injections for Tendon Pain

In some recalcitrant cases where there is marked hypersensitivity and pain that impedes engagement in the appropriate rehabilitation - Injections can be helpful adjuncts. Injections should be done under ultrasound guidance to ensure minimal trauma and maximise the effectiveness. It is thought that all types of injections have a beneficial effect by hydrodissecting or stripping some of the pathological nerve endings that infiltrate a degenerative tendon,14,15 but most clinicians would avoid corticosteroid as these may have atrophic effects on the already very slow tendon remodeling process. 16 However, just like any tool,

cortisone is not all bad. If you need to reduce inflammation or tissue thickening, then cortisone is potentially a great tool, such as when there is bursitis or scarred tendon pully trapping a tendon as with a trigger finger.

Here is a tendon stripping P-R-P injection shown with the achilles tendon in cross section, so it looks like an oval structure. The needle enters from the side and the injection hydrodissects the neurovascular ingrowth from front of the achilles tendon. This, or prolotherapy injections, can also be performed around other tendons for a similar effect and purpose.

When performed, injections need to be:

- Accurately guided

- Combined with an individualised plan for rehabilitation

Reference List

1. Benjamin M, Kaiser E, Milz S. Structure-function relationships in tendons: a review. J Anat. 2008 Mar;212(3):211–28.

2. Pingel J, Lu Y, Starborg T, Fredberg U, Langberg H, Nedergaard A, et al. 3-D ultrastructure and collagen composition of healthy and overloaded human tendon: evidence of tenocyte and matrix buckling. J Anat. 2014 May;224(5):548–55.

3. Cook JL, Purdam CR. Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2009 Jun 1;43(6):409–16.

4. Cook JL, Rio E, Purdam CR, Docking SI. Revisiting the continuum model of tendon pathology: what is its merit in clinical practice and research? Br J Sports Med. 2016 Oct;50(19):1187–91.

5. Docking SI, Cook J. Pathological tendons maintain sufficient aligned fibrillar structure on ultrasound tissue characterization (UTC). Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015 Jul 1;n/a-n/a.

6. Khan KM, Scott A. Mechanotherapy: how physical therapists’ prescription of exercise promotes tissue repair. Br J Sports Med. 2009 Apr;43(4):247–52.

7. Rees JD, Stride M, Scott A. Tendons – time to revisit inflammation. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Nov;48(21):1553–7.

8. Malliaras P, Barton CJ, Reeves ND, Langberg H. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes : a systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness. Sports Med Auckl NZ. 2013 Apr;43(4):267–86.

9. Rio E, Moseley L, Purdam C, Samiric T, Kidgell D, Pearce AJ, et al. The pain of tendinopathy: physiological or pathophysiological? Sports Med Auckl NZ. 2014 Jan;44(1):9–23.

10. Rio E, Kidgell D, Moseley GL, Gaida J, Docking S, Purdam C, et al. Tendon neuroplastic training: changing the way we think about tendon rehabilitation: a narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Sep 25;bjsports-2015-095215.

11. Hackett L, Millar NL, Lam P, Murrell GAC. Are the Symptoms of Calcific Tendinitis Due to Neoinnervation and/or Neovascularization?: J Bone Jt Surg. 2016 Feb;98(3):186–92.

12. Serafini G, Sconfienza LM, Lacelli F, Silvestri E, Aliprandi A, Sardanelli F. Rotator Cuff Calcific Tendonitis: Short-term and 10-year Outcomes after Two-Needle US-guided Percutaneous Treatment— Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. Radiology. 2009 Jul 1;252(1):157–64.

13. Gerdesmeyer L, Wagenpfeil S, Haake M, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic calcifying tendonitis of the rotator cuff: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003 Nov 19;290(19):2573–80.

14. Shalabi A, Svensson L, Kristoffersen-Wib... M, Aspelin P, Movin T. Tendon injury and repair after core biopsies in chronic Achilles tendinosis evaluated by serial magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Sports Med. 2004 Oct;38(5):606–12.

15. Abate M, Verna S, Di Gregorio P, Salini V, Schiavone C. Sonographic findings during and after Platelet-Rich-Plasma injections in tendons. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014 May 8;4(1):29–34.

16. Speed CA. Corticosteroid injections in tendon lesions. BMJ. 2001 Aug 18;323(7309):382–6.